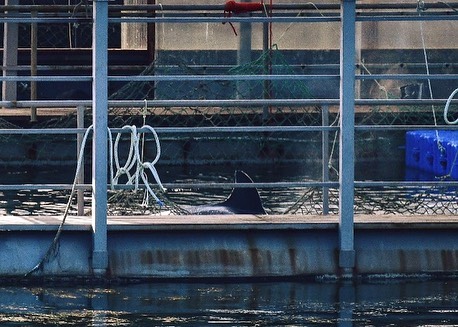

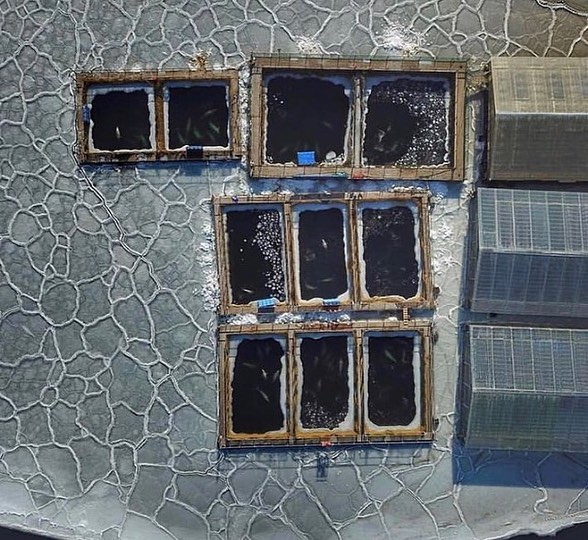

In November 2018 news began to surface that 101 wild-caught whales were being held captive at the Center for Adaptation of Marine Mammals in Srednyaya Bay, near Nakhodka, Russia. Under the ownership of TINRO, a Pacific Fisheries Research Center, the facility was quickly renamed “The Whale Prison” by the media due to its abhorrent conditions. Captured during the summer, 90 beluga whales and 11 killer whales arrived at the Whale Prison between July 16 and October 21 and were packed into small, overcrowded pens that barely provided the animals with enough space to swim. All had been subjected to the horrors of wild-capture and the scarring trauma of separation from their family pods – it proved too much for one killer whale who died during the capture process.

The 11 surviving killer whales were named and sexed as follows:

- Alexandra, F, 1 year old

- Vasilievna, F, undisclosed age

- Vitas, M, 2 years old

- Gaika, F, 2 years old

- Zina, F, 4 years old

- Zoya, F, 4 years old

- Kirill, M, 1 year old

- Leha, M, 4 years old

- Tihon, M, 3 years old

- Forest, M, 2 years old

- Harja / Kharya, F, 4 years old

Photo via Free Russian Whales.

The four companies responsible for their capture (LLC Oceanarium DV, LLC Afalina, LLC Sochi Dolphinarium and LLC Bely Kit) wished to sell the whales into the Chinese marine park industry where they could collectively fetch a price of $68.5 million, if not more. However, the capture of cetaceans for the purpose of commercial export is illegal in Russia and intense public outcry alerted the authorities to the potentially criminal actions of these four companies. A veterinary inspection by government officials found up to 15 of the beluga whales were less than a year old violating Russian law which prohibits the capture of un-weaned calves. The Vladivostok Interdistrict Environmental Proseutor’s Office then discovered a number of serious violations with the capture permits which sparked a lengthy investigation that would continue until mid-2019.

With it becoming increasingly clear that these whales had been illegally captured, public outcry continued to intensify and calls to release the whales found support across the globe. However, by December, the situation was becoming dire for the whales in Srednyaya bay. Due to the frigid temperatures in Primorsky Krai, the water in the bay began to freeze over and the tens of malnourished calves who struggled to maintain a healthy blubber supply were at great risk of succumbing to hypothermia. Soon enough, sheets of snow-covered ice surrounded the sea pens and the captors claimed three of the youngest beluga whales had “mysteriously escaped”, although it’s more likely these calves perished from the cold temperatures, stress, disease, or malnutrition. The captors incorporated a high death toll into their total take which is why such an obscene number of belugas were captured; around a third were expected to die before finding a buyer.

In mid-January 2019, shortly after these deaths were reported, the Whale Prison underwent a three-day audit organised by the Federal Security Service (FBS) featuring biologists, veterinarians and even the head of the Criminal Investigation Department of Nakhodka. They found “a complete absence of sanitation and activities aimed at preventing pathogens from infecting the animals” and confirmed that the facility was covered in thick, dense ice. Skin samples taken from all 11 orcas were found to have staphylococcus, candida, and other opportunistic infections. Their skin was described as being “thickly seeded with bacteria” and covered in lesions possibly caused by fungal infections.

Photo via Free Russian Whales.

A follow-up inspection by the Primorsky Environmental Prosecutor’s Office on January 30th exposed the near-death state of Kirill (Cyril), a 1-year-old male killer whale, who was seen floating belly-up in his holding pen. He was described as being in poor condition and suffering from frostbite and pneumonia. It’s believed Kirill died the day after the inspection on January 31 2019.

Photo via Free Russian Whales.

Upon the completion of these investigations, the owners of the “Whale Prison” were charged with cruelty to animals by the Investigative Committee of Russia for the Khabarovsk Territory in late February and talks of releasing the whales were about to become a reality. Investigators announced they would “take comprehensive measures to return all marine mammals to their natural habitat” and Russian Minister of Natural Resources & Environment, Dmitry Kobylkin, said in a statement: “It’s absolutely clear to us that the orcas need to be released. No one has any objections today to releasing them, but the important thing is to do it correctly, so as not to lose a single individual.”

While Russian authorities began to develop a plan of rehabilitation and re-adaption for the whales, the health of the orcas and belugas at the Whale Prison started to rapidly deteriorate. Veterinarians who conducted another inspection in March discovered more lesions, dark blotches, and other skin disorders on the surviving animals which appeared to be signs of worsening fungal, bacterial, and viral infections. On top of that, at least one of the orcas had missing and fractured teeth. According to Dr. Tatyana Denisenko, the unhealthy state of the whales was a direct result of their adverse living conditions, characterised by poor sanitation, poor water quality, sources of stress and the presence of significant numbers of microorganisms of anthropogenic origin. Experts warned that the limited space and severe overcrowding would contribute to the further spread of infections and illnesses throughout the facility.

Photo via Free Russian Whales.

Photo via Free Russian Whales.

Action needed to be taken but was release feasible? Ecologists claimed at least 15 of the 87 belugas were too young to survive on their own and would die if released. All of the whales had become heavily reliant on humans during the past year and lacked the skills needed to survive in the wild. Despite this, Deputy Prime Minister Alexei Gordeyev announced that the whales would be moved to a “Center for the Maintenance of Large Marine Animals” on Russky Island for rehabilitation purposes, but there was one big problem – no such facility existed. At the time, it appeared as though the Russian government was intending to keep all 97 whales in their overcrowded, unsanitary sea pens until a rehabilitation center was built. During this time, head trainer at the Whale Prison, Andrei Nasonov, told the media that he would continue to train the whales for dolphinariums until a final decision was made by the government, potentially tarnishing any future efforts to successfully rehabilitate and release them.

By the beginning of April things took a far more positive turn. Governor of Primorsky Krai, Oleg Kozhemyako, signed a joint agreement with Director of the Whale Sanctuary Project, Charles Vinick, and world-renowned explorer and environmentalist, Jean-Michel Cousteau, to rehabilitate and release the orcas and belugas held at the Whale Prison. Part of the agreement involved carrying out a proper evaluation of each animal to determine its feasibility for release. The team also signed a memorandum of mutual understanding with VNIRO declaring the unification of efforts, cooperation, and coordination regarding the rehabilitation and release of the whales.

Photo provided by Free Russian Whales and Katerina Studios.

At the end of April, Vinick and Cousteau’s team of marine mammal experts had completed their evaluation of each whale and determined all 87 belugas and 10 killer whales could be rehabilitated and released, with no identified scientific reason as to why this may not be possible for individual animals. The experts speculated the orcas may require just 1-2 months of rehabilitation prior to their release due to the minimal training they had received. The belugas also only required short-term rehabilitation, excluding the small number of un-weaned calves who would require a more intensive variant.

Ignoring expert advice, Russian officials then announced in May that they were planning to release the whales into Srednyaya Bay, nearly 800 miles south of where they were initially captured in Nikolai Bay last summer. Returning them to their capture location yields the highest prospects for social reintegration, successful foraging and long-term survival but Vladislav Rozhnov, head of the Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Environment, deemed it too costly. Instead he wished to potentially jeopardise any chance these whales had at a successful release by dumping them into Srednyaya bay.

Fortunately, some more positive news surfaced. Throughout the month of June the four companies responsible for capturing the orcas and belugas held at the Whale Prison were fined a total of 150.276 million rubles ($2,348,814) for violating fishing regulations. Bely Kit LLC, Far East Oceanarium LLC, Sochi Dolphinarium LLC and Afalina LLC were fined 28.1, 56.4, 37.6 and 28.176 million rubles, respectively.

After months of no action the release process suddenly began on June 20 when two orcas (Leha and Vasilievna) and six belugas were removed from their filthy, overcrowded sea pens in Srednyaya Bay and transported to the village of Innokent’yevka in the Khabarovsk Territory. From here they were moved to Cape Perovskogo where veterinarians checked them over and attached satellite tags to allow scientists to track their movements and collect behavioural data.

Photo by VNIRO.

It was reported all of the whales were in good health but videos of the release effort showed highly stressed animals and blood-stained foam pads, either from injuries sustained during the transportation process or possibly the attachment of the satellite tags, depending on the method used. The whales were then released into the Gulf of Sakhalinon June 27 without any rehabilitation. Traumatised and confused after spending six days confined to small transit containers, the orcas stayed close to shore for the first few hours before moving to open water. The belugas headed straight to sea. The complete absence of any rehabilitation whatsoever was greatly concerning. These animals had spent the last year in captivity, being hand-fed by human trainers who acted as their sole source of food. They were then dumped in the sea and forced to fend for themselves. Could these calves survive on their own? Their chances were slim.

Photo by VNIRO.

On July 11 three more killer whales started the long journey back to the wild. Employees at the Whale Prison removed the transparent roof of the floating building housing the killer whale pens, used nets to move one male (Vitas) and two females (Alexandra and Zina) onto fabric stretchers, and then lifted and lowered them into containers of water on three trucks. The remaining animals were clearly agitated by the sudden activity as they vocalised loudly and slapped their tails against the water.

Once securely in their travel containers the whales spent four days traveling to the town of Innokent’yevka of the Nikolaevskiy District where they started the final stretch of their journey – a five-hour drive to Cape Perovskogo. Upon their arrival on July 16, the whales were fitted with satellite tags and given a one-hour massage to stimulate blood flow in their tails prior to their release. They were then lowered into the water and set free into the Gulf of Sakhalin.

The whales grouped together and swam 300 metres away from the coast in an easterly direction. Their caretakers followed them for 15 miles and described their behaviour as calm, sometimes increasing their speed and jumping high from the water. While at one point the orcas distanced each other by 200 metres they reunited and swam off as a pod towards the open sea.

Less than two weeks after her release disturbing footage emerged of Alexandra, a two-year-old killer whale released on July 16th, interacting with fishermen and begging for food. Data collected from the satellite tags revealed that the two older orcas she was released with, believed to be Zina and Vitas, had since travelled nearly 200km away from the release site to the Gulf of Nicholas. However, Alexandra remained close to the release site in Sakhalin Bay, alone and unable to fend for herself. Fortunately, the two orcas released on June 26th, Leha and Vasilievna, remained together. Once free, they reportedly travelled to Academy Bay, hunted there, and then went to the Uda Gulf where they continued to hunt for the following three days. After hunting in the Gulf, the whales moved along the coast to the area north of Ayan village. On July 10, Leha and Vasilievna headed south and stayed in Borisov Bay up until July 12 when they travelled to the Shantar Islands. This is known territory for wild orca pods, although it’s currently unknown if either of the whales met up with wild orcas.

By August 1 a third group of killer whales were beginning their journey to the release site. This time Tihon, Gaika and Zoya were removed from their sea pens on and handled into transport containers to undergo the gruelling journey to Cape Perovskogo. For the first time Greenpeace Russia were able to observe the transport process. They documented ice being regularly added to the transport containers to prevent the whales from overheating, protective ointment being rubbed into their exposed skin and regular massages of their pectoral fins and tail flukes to keep their muscles healthy. Despite weather conditions deteriorating during the last of the journey, all three whales were lifted from their containers, satellite tagged and then successfully released into the Sea of Okhotsk on August 6. This third release left just two killer whales at the Whale Prison – Harja (also known as Kharya) and Forest – who underwent the same journey beginning on August 22 and were released alongside six beluga whales on August 27.

Photo by VNIRO.

By the end of August all 10 of the Whale Prison’s killer whales were free, but that wasn’t the only good news. On August 20 Vasilievna was seen travelling, hunting and sharing food with a pod of seven killer whales. Was this pod her long lost family? We’ll never know for sure but the fact she managed to reintegrate into a wild pod is fantastic news.

Photo by Grigory Tsidulko via VNIRO.

More positive news followed on September 10 when Zina, a 5-year-old killer whale, was sighted travelling with a pod of 14 killer whales. Both females had successfully reintegrated into wild pods – something that was vital to their long-term survival. They could finally put the horrors of the Whale Prison behind them and live long, and happy lives.

To view more photos of these successful wild integrations click HERE.

Photo via Free Russian Whales.

Unfortunately, while the killer whale pens were empty, the Whale Prison still housed belugas. 12 had been released but 75 remained. Between September 28 and October 2 14 beluga whales were taken to the release site and released, followed by 11 more between October 18 and October 23. This conveniently left 50 belugas at the Whale Prison which happened to be the exact number of beluga whales Chinese companies had pre-paid for to supply dolphinariums in China. The future of these remaining belugas was in doubt. Would they be released or would they be sold and forced to live a life inside the barren confines of a concrete tank? On October 14 Minister of Natural Resources and Ecology of Russia, Dmitry Kobylkin, discussed this contract with Chinese representatives and decided to release all of the remaining belugas – a process due to start in November.

In line with Kobylkin’s decision, the initial process of loading the whales onto two VNIRO vessels, the “Zodiac” and the “Professor Kaganovsky”, began on November 5, but was temporarily suspended shortly after due to harsh weather conditions. The next day 19 belugas were loaded onboard the “Professor Kaganovsky” and 14 belugas were loaded onto the “Zodiac”. Both set sail for Uspeniya Bay with “Professor Kaganovsky” arriving on November 7 followed by “Zodiac” on November 10.

Photo by VNIRO.

Having arrived first, “Professor Kaganovsky” unloaded and released its 19 beluga whales and returned to Srednyaya Bay to pick up the last 17 belugas held at the Whale Prison. By November 10 “Professor Kaganovsky” had re-joined “Zodiac” in Uspeniya Bay and both vessels unloaded and released the last 31 belugas due to be set free. Specialists from the Boarder Guard Department of the Primorsky Territory documented the release of each whale and three individuals were equipped with satellite tags for further monitoring. For the first time in over a year the Whale Prison’s sea pens were empty. All 10 killer whales and 87 belugas had been released back into the wild. The Whale Prison was no more.

Photo by VNIRO.

To see more photos of each release effort click on the links below:

- Release #1 – Two killer whales (Leha and Vasilievna) and six beluga whales

- Release #2 – Three killer whales (Alexandra, Zina and Vitas)

- Release #3 – Three killer whales (Tihon, Gaika and Zoya)

- Release #4 – Two killer whales (Harja and Forest) and six beluga whales

- Release #5 – 14 beluga whales

- Release #6 – 11 beluga whales

- Release #7 – 31 beluga whales