In the wild, despite centuries of sharing the ocean, there has only been one reliable report of an orca injuring a human being. The attack occurred on September 9, 1972, when 18-year-old Hans Kretschmer was bitten by an orca whilst surfing at Point Sur. Kretschmer noticed some sea lions playing in the waves prior to the attack, leading him to believe the sudden nudge he received was a curious sea lion. When he turned to look at the instigator, he realised he was terribly mistaken. A six-meter-long killer whale had bitten down on his leg with incredible force. In an attempt to defend himself, Kretschmer punched the animal repeatedly, causing it to suddenly let him go. Once free, the shock-ridden surfer desperately swam 40 meters to shore, a swim which he survived. Upon seeking medical attention, Kretschmer’s doctor commented: “it looks like someone chopped your leg with a sharp axe.”

The injury he sustained was just as graphic with three teeth penetrating bone: narrowly missing a major artery with surgical precision. It required 100 stitches to fix. Although Hans Kretschmer holds the title as the only human being to be seriously injured by a wild orca, there have been five other incidents between humans and wild orcas.

In the early 1910s, a pod of Antarctic type B killer whales, otherwise known as pack ice orcas, attempted to tip an ice floe on which a Terra Nova Expedition photographer and a sledge dog team were standing. Pack ice orcas specialise in hunting seals by wave-washing them off ice floes. Witnesses theorized the orcas mistakenly identified the barking dogs as a family of seals and initiated their unique hunting technique. Fortunately, no one was injured.

A few months before the attack on Hans Kretschmer in September 1972, Dougal Robertson’s 43-foot wooden schooner, named Lucette (Lucy), was damaged by a pod of killer whales and sunk 200 miles west of the Galapagos Islands on June 15, 1972. Everyone on board managed to escape on an inflatable life raft and a solid-hull dinghy. After 38 days as castaways, the small group of people was sighted and rescued by the Japanese fishing trawler Tokamaru. No one was injured.

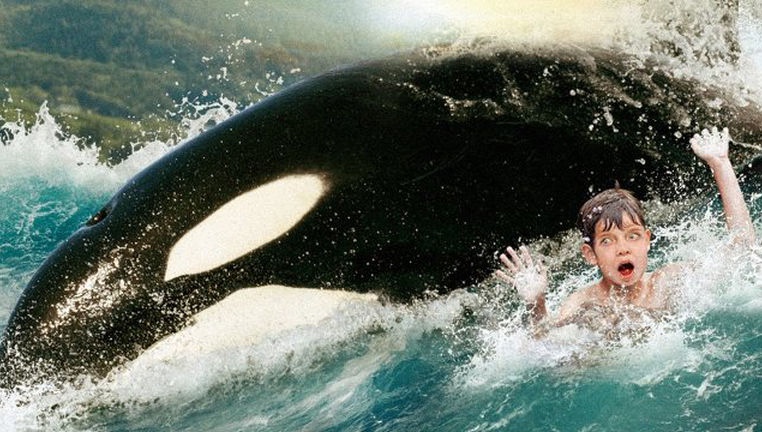

Almost 33 years later, in August 2005, 12-year-old Ellis Miller was swimming in 4ft deep water in Helm Bay, near Ketchikan, Alaska, when he was nudged by a 25ft transient killer whale. The whale bumped Miller on the left side of his chest and shoulder, then arched around him before returning to deeper waters. Experts believe the orca mistakenly identified the boy as a splashing harbour seal (which frequent the bay’s waters) then realised its mistake and aborted the attack. Miller did not sustain any injuries.

Photo via YoungWritersGuide.

In 2011, two crewmembers of the BBC’s documentary Frozen Planet were targeted by a group of orcas who attempted to swamp their 18-foot zodiac boat with a wave washing technique. The crew filmed over 20 different attacks on seals using this technique within a 14-day period, unaware the pod would test it out on them too. The orcas were described as very tolerant to the filmmakers’ presence, and their attacks on seals were described as training exercises for young calves in the group. Perhaps the pod was making use of this new, more challenging “ice floe” to test their attentive youngsters. Regardless, no one was injured. Watch the incident below:

The most recent incident occurred on February 10, 2014. Whilst free diving in Horahora Estuary, near Whangarei in northern New Zealand, 23-year old Levi Gavin was suddenly approached by an orca who grabbed a catch bag (filled with crayfish) attached to his arm and pulled him beneath the surface. Gavin was dragged for 40 seconds when the rope attaching his arm to the bag finally became loose and he was able to escape. Although his arm became numb, he managed to float to the surface by removing his weighted belt and was aided by his cousin who brought him to some nearby rocks. Once his arm regained feeling and strength, Gavin went to Whangarei Hospital where it was established he did not sustain an injury during the attack.

Because of the stress involved in being deprived of everything that is natural and important in captivity, orcas have been held responsible for hundreds of attacks, tens of injuries, and the deaths of four humans. Six incidents have occurred in the wild over a period of around 100 years (1910s – 2014), none of which proved fatal. Yet, within less than a fifth of that time (1991 – 2010), 82 aggressive incidents occurred in captivity, four of which proved fatal, at least 9 others causing serious injuries from torn ligaments to broken bones and internal bleeding.

One of the most infamous captive orca attacks occurred at SeaWorld San Diego in November 2006. Kasatka, a 17ft long, 29-year-old, female orca attacked Kenneth Peters – the marine park’s most experienced trainer. Peters was working with Kasatka during a Shamu Show and dived into the pool to perform a water work behaviour. He reached a depth of 10-15ft and was waiting for Kasatka to touch his foot when he heard a loud distress vocalisation. He later learned this loud call came from Kasatka’s almost-two-year-old calf, Kalia, who was calling for her mother whilst separated in a different pool. Upon hearing her daughter’s call, Kasatka turned on Peters and grabbed both of his feet in her jaws. She held him underwater for almost a minute, violently rag-dolling him beneath the surface, before slowly bringing him to the surface, spiralling upward and blowing bubbles as she rose.

Every time Peters’ colleagues slapped the water (a signal for Kasatka to return to the stage) she would only bite down on Peters harder. She responded the same way if Peters tried to pull his foot out of her mouth. Kasatka was keeping him out of reach of the other trainers and away from the sides of the pool. She then pulled him beneath the surface again, thrashed him around, and took him all the way to the bottom of the 36ft deep pool where she laid against him and held him there for around a minute. Once Peters had gone limp, Kasatka finally brought him to the surface again. She released Peters and he managed to make it over a net (which Kasatka also crossed, coming after Peters) and escaped the pool via the slide-out area. Kasatka had broken Peters’ left foot during the attack and he sustained multiple puncture wounds. Regardless, he escaped with his life. Watch the footage of the incident in its entirety below:

Kenneth Peters claims Kasatka’s “aggression had come as a total surprise”. The attack occurred as a result of Kalia’s distress call, who had been separated from her mother briefly so Kasatka could entertain an audience of around 500 people. According to SeaWorld’s own animal profiles, Kasatka finds “being separated from other whales/calf” aversive. As SeaWorld San Diego’s most experienced orca trainer, who had worked with Kasatka for many years, Peters would’ve been more than aware of this fact. Yet, he and his colleagues demonstrated a complete disregard for Kasatka’s triggers and he almost lost his life as a result.

The heightened level of aggression towards humans in captivity is a clear indicator of how unnatural and unnecessarily dangerous orca captivity is. Here’s a collection of orca attacks caught on camera at marine parks:

Shamu, the original, attacking Annette Eckis at SeaWorld San Diego (April 1971). She recalls the incident almost 40 years later.

Orky 2 crashing into John Silick at SeaWorld San Diego (1987).

Taku displacing a trainer in the water at SeaWorld Orlando (1994).

Orkid and Splash attacking Tamarie Tollison at SeaWorld San Diego (2002).

Kyuquot attacking Steve Aibel at SeaWorld San Antonio (2003).

Ku lunges at her trainer at Port of Nagoya Aquarium (Mid-2000s).

Orkid attacking Brian Rokeach at SeaWorld San Diego (2006).

Freya attacking a trainer during a show at Marineland Antibes (2008).

Shouka repeatedly lunges at her trainer at Six Flags Vallejo (2012).

Lolita lunges at guests at Miami Seaquarium (2012).