Although the transient population of orcas in captivity is rising thanks to cruel capture operations in Russia, the vast majority of captive orcas originate from the tightly-bonded lineage of resident (fish-eating) killer whales. Research suggests adult male offspring of resident populations will live with their mothers for their entire lives, only temporarily separating from her to breed, equating to spending up to 70 percent of their time within one body length of their mother until the day she dies. Although females may disperse from their mother’s pod to raise their own young, they can often be found close by and will return to visit their mother. In fact, mothers are so vital to their offspring that, as research suggests, female killer whales will experience the menopause to live longer to care for their adult young.

Photo courtesy of Hysazu (Instagram)

The death of a mother can have a devastating impact on her offspring. Within the first year of their mother’s death, young males were 3 times more likely to die than males whose mothers were still alive. Adult males over the age of 30 were 8 times more likely to perish, with older daughters 2.7 times more likely to die. Resident populations are so family-orientated that the only way of joining a matriline is by being born into it, and the only way of leaving it is through death. Similarly to humans, family is of great importance to orcas. Despite this, marine parks across the globe insist on separating offspring from their mothers. 20 mother and calf separations have occurred in captivity, 70% of which involved calves under the age of five. Only four of these separations were necessary either due to violent inexperienced mothers or the requirement for superior medical care at a different facility.

Mother and calf separations are emotionally devastating for both parties. Orcas have been known to injure themselves during, and fall in states of depression after, such cruel events. Four notable separations reveal the heartbreaking truth, they are as follows:

Katina and Kalina

On February 12th, 1990, four-year-old Kalina was separated from her mother, Katina, and sent to SeaWorld Ohio. After the separation, Katina, who was not an overly vocal whale, reportedly spent the night alone in the corner of her tank, shivering and screeching, emitting heart-wrenching vocalisations because of her loss. Despite the gates to their tanks being open, Katina’s tank mates (including Katina’s one-year-old calf, Katerina) left her alone to grieve after checking on their sorrow-filled pod member.

Photo submitted by Valentin666.

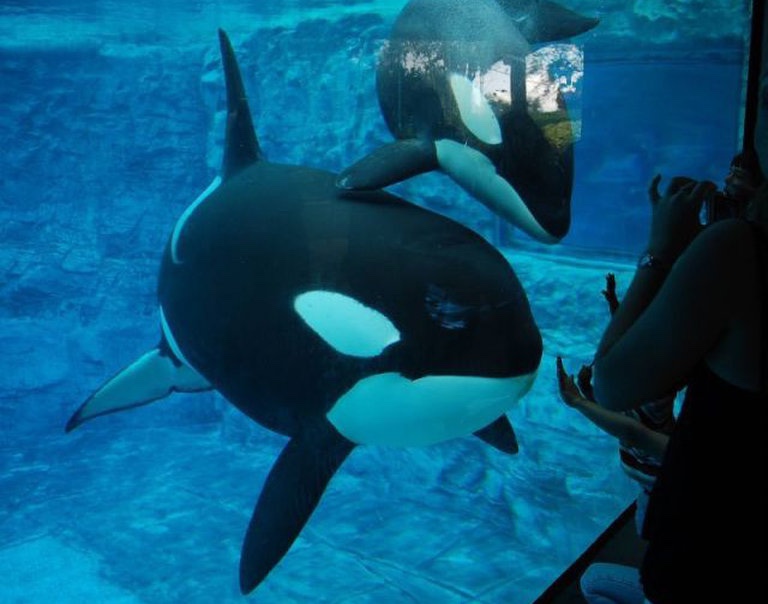

Kasatka and Takara

Fourteen years after Katina and Kalina were separated, Kasatka was separated from her first-born calf, Takara, on April 24th, 2004. According to SeaWorld’s killer whale profiles, Kasatka is a protective mother and finds “being separated from other whales/calf” aversive. Additionally, it details Kasatka and Takara would both spend “90% of their time on opposite sides of the gate” when separated into different tanks at night. Despite being aware of the emotional attachment and strong bond between Kasatka and Takara, SeaWorld insisted on separating the mother-daughter pair when Takara was 12 years old. Kasatka reacted in a similar way to Katina, emitting loud distress vocalisations after being separated from her daughter.

Although SeaWorld had separated Takara from her devoted mother, they weren’t done with her yet.

Photo submitted by Jason Lee Scott.

Takara and her calves (Kohana and Trua)

Just like Kasatka, Takara was a protective and loving mother becoming very attached to all of her calves. However, less than two years after she was separated from her mother, Takara was separated from her first-born calf, Kohana, in February 2006 and her second-born calf, Trua, in February 2009. Kohana was sent to Loro Parque whereas Takara was sent to SeaWorld San Antonio, whilst Trua remained at SeaWorld Orlando.

Photo submitted by Terry Hardie.

Before the final separation occurs, SeaWorld applies a weaning process where mothers and their calves are forced to spend less and less time together at their resident facility. Takara’s complete attachment to her calves, in this case to Trua, was demonstrated during a performance of ‘Believe’. According to a member of the audience, the show was running smoothly as all whales were complying with their cues. However, mid-way through the show, Takara raced out of the back pool and went to a gate her son Trua was trapped behind. She reportedly “jammed her rostrum up against the gate and began emitting god-awful, high-pitched distress calls in an attempt to get to her son.” Trainers attempted to calm Takara but their efforts were in vain and the show had to be cancelled. Takara and Trua were reunited later that day. As periods of separation from her son increased, regulars claimed Takara fell into a state of depression. Considering Takara’s extreme aversive reaction to being separated from her son simply via a gate, a cross-country separation must’ve been unimaginably devastating for Takara and Trua alike.

Photo submitted by OrcaLover.

Kalina and Skyla

Just like Kohana, Skyla was separated her mother, Kalina, in February 2006 and sent to Loro Parque on breeding loan despite having just turned 2 years old. On the day of the separation, as Skyla was being harnessed and craned out of the pool, Kalina became incredibly distraught and began ramming into the gate separating her from her daughter. Her relentless attempts caused her to ‘break open her face’ resulting in significant lacerations.

Photo via Orca Tank Wikia

Photo via Orca Tank Wikia.

Separating mothers and calves has proven to be particularly detrimental to female calves and their experience of motherhood. In October 2005, 16-year-old Kayla gave birth to her first calf at SeaWorld San Antonio. Kayla immediately became aggressive with her calf and pushed it against the glass of her tank, picked it up and tossed it, fluked it (hit it with her flukes) out of the pool and onto the slide out, and held it up against the gates. Kayla’s brutal attack on her calf only stopped when a gate to an adjacent pool was opened, which she swam through and allowed herself to be separated from the calf. Kayla, who was separated from her mother at merely 2 years old, never learned how to properly care for a calf leading to the violent rejection of her own. The calf, later named Halyn, was moved to animal care and had to be hand-raised by her trainers. She died two years later.

Photo submitted by HaH.

A more recent example of calf rejection occurred at Loro Parque. Kohana, an 8-year-old female, gave birth to her first calf, Adán, in October 2010. SeaWorld, who sent Kohana on breeding loan to Loro Parque in 2006, separated her from her mother at 3 years old. As a result, just like Kayla, Kohana was unable to learn how to care for calves properly which resulted in her rejecting Adán and her second calf, Victoria, who was born in 2012.

Photo submitted by Estel Moore.